This was such a unique article I decided to share it. First though let me provide some personal information about my family and myself:

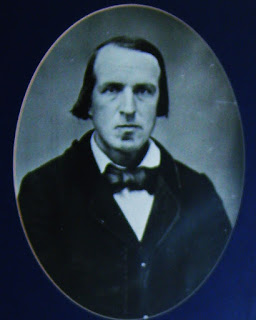

.....My Great great grandfather was Mathew Fitzgerald (in the picture above). Family lore says that he was an abolitionist who willingly reenlisted with the Union in 1864 after returning home for visit his family and 4 children (this picture was taken during that visit). He was adamantly against the "scourge of slavery" and wanted to help end the war that he thought would end slavery. He was a "Lincoln Republican",and died in a confederate prison camp a year after the photo was taken (using an advanced scientific invention....the pinhole camera).

.....My Great great grandfather was Mathew Fitzgerald (in the picture above). Family lore says that he was an abolitionist who willingly reenlisted with the Union in 1864 after returning home for visit his family and 4 children (this picture was taken during that visit). He was adamantly against the "scourge of slavery" and wanted to help end the war that he thought would end slavery. He was a "Lincoln Republican",and died in a confederate prison camp a year after the photo was taken (using an advanced scientific invention....the pinhole camera).

.....Below is a picture of myself and future wife as I prepared to travel from our home in Connecticut to a new home in South Carolina. The article below proposes evidence that supports how poverty persists and how it is eradicated. The article asserts and supplies evidence for the assertion that a better life can be the result of a willingness to pick up stakes and move. It also cites how certain localities generate more "escapees" from poverty that others.

.....The article below actually discusses what has been observed to work in eradicating poverty as well as detailing what has not worked. The examination of factors that appear to lead people out of poverty should be, I think, very carefully studied. This suggests additional studies, that in my mind, should include what is going on in the schools that serve these regions!....I found this article thought provoking:

The irony is that as blacks drifted farther from the Republican party, a similar group became its base. Appalachian whites suffer from many of the same social ills as working-class blacks: broken families, substance abuse, poor health, and high poverty. The two groups differ in important ways, but the past 80 years of Appalachian history nonetheless offer lessons about how modern public policy can assist black Americans. Early anti-poverty efforts focused largely on the white population. In an era of “colored” drinking fountains and separate schools, federal aid was as segregated as a southern lunch counter. Social Security excluded agricultural and domestic laborers at a time when most African Americans worked in those professions. Many dark-skinned members of the Greatest Generation never enjoyed the fruits of the GI Bill because of racial discrimination by colleges. It was, as Ira Katznelson argued in an explosive book, a type of affirmative action — for white people.Katznelson’s arguments, though hardly new, have recently gained traction. The idea of paying reparations for slavery has reentered the national debate, and there’s a growing fear, to borrow the words of The Atlantic’s Ta-Nehisi Coates, that “the effects of a social safety net engineered for the aid of some and the hindering of others is [sic] still with us.” To fix the problem, some say, society need merely invert the racist policies of the past. Implement a “domestic Marshall Plan” for black America, says Chicago radio host Salim Muwakkil.

– J. D. Vance, a graduate of Yale Law School and a Marine Corps veteran, is working on a book about the social mobility of the white working class. He can be reached through his Twitter account, @jdvance1. For more on the plight of Appalachia, see “Left Behind,” Kevin D. Williamson, National Review, December 16, 2013. This article originally appeared in the September 22, 2014 issue of National Review.

.....The article below actually discusses what has been observed to work in eradicating poverty as well as detailing what has not worked. The examination of factors that appear to lead people out of poverty should be, I think, very carefully studied. This suggests additional studies, that in my mind, should include what is going on in the schools that serve these regions!....I found this article thought provoking:

==============================================================

Consigned to ‘Assistance’ From the September 22, 2014, issue of National Review By J. D. Vance

It’s sometimes easy to forget that the Republican party’s proudest moment was the emancipation of the American slave. Indeed, for decades after Lincoln gave his life for the Union, black America voted overwhelmingly Republican. But after FDR brought promises of help to the needy and Goldwater fought the 1964 Civil Rights Act (for what Martin Luther King Jr. called non-racist but still-foolish reasons), the party never recovered its standing with black voters.

The irony is that as blacks drifted farther from the Republican party, a similar group became its base. Appalachian whites suffer from many of the same social ills as working-class blacks: broken families, substance abuse, poor health, and high poverty. The two groups differ in important ways, but the past 80 years of Appalachian history nonetheless offer lessons about how modern public policy can assist black Americans. Early anti-poverty efforts focused largely on the white population. In an era of “colored” drinking fountains and separate schools, federal aid was as segregated as a southern lunch counter. Social Security excluded agricultural and domestic laborers at a time when most African Americans worked in those professions. Many dark-skinned members of the Greatest Generation never enjoyed the fruits of the GI Bill because of racial discrimination by colleges. It was, as Ira Katznelson argued in an explosive book, a type of affirmative action — for white people.Katznelson’s arguments, though hardly new, have recently gained traction. The idea of paying reparations for slavery has reentered the national debate, and there’s a growing fear, to borrow the words of The Atlantic’s Ta-Nehisi Coates, that “the effects of a social safety net engineered for the aid of some and the hindering of others is [sic] still with us.” To fix the problem, some say, society need merely invert the racist policies of the past. Implement a “domestic Marshall Plan” for black America, says Chicago radio host Salim Muwakkil.

No one doubts the injustice of Jim Crow. But before foisting a more robust social safety net “engineered for the aid of some” on black Americans, it’s worth assessing whether we missed the mark on the first go-round. And if we failed, we should figure out why.

In 1965, Lyndon Baines Johnson extended the social safety net to all populations. Yet despite racially neutral intent, a heavy emphasis on rural whites persisted. Two federally chartered organizations — the Depression-era Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) and Johnson’s Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC) — pumped millions of development dollars into predominantly white rural locales. There was no corollary in black America — no Urban Aid Commission to flood inner cities with aid. Appalachia’s closest economic and cultural cousin is the Mississippi Delta region, a veritable Appalachia for blacks. Yet the Delta Regional Authority, explicitly modeled after the ARC, spent its first dollar in 2000 — 35 years after LBJ made Appalachia the focus of the War on Poverty.

The aid came not just in the form of direct welfare payments, but also as government jobs. The country-music anthem “Song of the South” tells a familiar tale: “Papa got a job with the TVA; we bought a washing machine and then a Chevrolet.” Thanks to the TVA, thousands of America’s rural white poor obtained high-wage government jobs. And the industrial infrastructure they built still dots the landscape: beautiful lakes birthed by hydroelectric projects and three-lane highways constructed with federal dollars. But there are now precious few jobs in Tennessee valleys and too few drivers on those wide mountain roads. If Papa bought a washing machine and then a Chevrolet, Junior is buying oxy or meth: West Virginia leads the nation in drug-overdose deaths, with Kentucky third and Tennessee eighth.

The scale of the investment is staggering. From 1965 until 1981, when the federal government began to scrutinize the cash flowing to Appalachia, federal appropriation to the ARC exceeded $1 billion (in today’s dollars) every single year. Even today, Congress sends about $80 million to the ARC; no other regionally focused entity spends more. As late as 2000, Appalachians received more federal money per capita than average, despite their minimal cost of living and the low number of federal employees in the region.

Twenty years after the ARC’s founding, the New York Times reported that the nation had spent billions on Appalachia with little gain. Its employment gap had persisted and even widened — during the worst of times, the unemployment rate was as much as five percentage points higher than the national average. Economically depressed Central Appalachia lost 26,000 jobs at a time when the U.S. economy added 7 million.

That was in 1985. Today, the inheritors of Katznelson’s affirmative action for whites occupy the lowest rungs of the socioeconomic ladder. West Virginia, Kentucky, northern Georgia, and South Carolina all nabbed more than their fair share of federal aid, but now they are among the poorest parts of the country. Inequality has grown faster in West Virginia than in any other state. When the New York Times compiled a national quality-of-life ranking, six of the bottom ten counties came from the same small corner of southeastern Kentucky.

Residents of these states suffer the worst consequences. In many Appalachian counties, inhabitants can expect to live only 67 years, more than a decade less than the average American. In the heavily white Rust Belt enclaves of Indiana and Ohio, children born poor have only a 6 percent chance of becoming wealthy, significantly worse than those from Newark (9.4 percent) or Salt Lake City (11.5 percent).

Alongside the grim statistics is a spiritual poverty more difficult to measure but easier to see. There’s the high-school teacher who has only once had a class without a pregnant student. The kindergartner who arrives at school in January without a shirt, so embarrassed that he forgot to put one on that he refuses to remove his thin jacket. The teenaged mother who lost track of her child — “She acted like she had lost her car keys,” her teacher later told me. Authorities found the baby with distant relatives more than 600 miles away. Behold the “winners” of FDR’s and LBJ’s brands of affirmative action.

Not all of these anti-poverty efforts failed. Many whites rode the GI Bill to a great education or assumed mortgages for wealth-building property when most blacks couldn’t. But there are millions of people whose family tradition is destitution: Their forebears were day laborers in the antebellum slave economy, sharecroppers after that, and then miners and steelmen until they couldn’t find jobs at all. The Treasury opened its wallet to change that, building homes, roads, and power plants in the hopes that some could escape the poverty trap. Is it shameful that these efforts were expended primarily in a way that excluded the black population? Certainly. Yet the failure of the effort gives us ample reason to question the wisdom of federally led development efforts no matter the intended beneficiaries. Government cannot create a sustainable economy, no matter how hard it tries. And traditional welfare, while defensible as a way of alleviating immediate deprivation, too often fails to place people on the road to self-sufficiency.

Yet there is more to glean from our government’s efforts to help Appalachia than a renewed skepticism of government aid. We’ve learned, painfully, that for the multigenerational poor, home might be the worst enemy. Appalachian loyalty to the land is the stuff of legend, yet the stubbornness of poverty in the region means that those who stay risk being poor forever. When the government paved thousands of miles of roads in Appalachia, it hoped to provide employment for the masses and infrastructure to sustain future economic growth. But the best and most lasting effect of those roads was to give people a faster way out. If we cannot improve the urban ghetto or the mountain hollow — and the evidence suggests we can’t — then the best anti-poverty program is a ticket to somewhere else.

Migration works not just because some areas suffer; it works because many areas don’t. Take, for instance, two small towns in southeastern Kentucky — Hazard and London. Each suffers from high rates of poverty. Yet Hazard’s children are more than twice as likely to earn a high income — much likelier than children from nearly every major American city. Subtle differences give clues about why. In Hazard, poor people are more likely to live in mixed-income neighborhoods, and intact families are the norm. London children, on the other hand, more often experience broken homes, and the poor live in income-segregated neighborhoods. As the eminent sociologist William Julius Wilson has argued, these segregated neighborhoods send thousands of subtle signals about acceptable (or unacceptable) behavior. Young students in eastern Kentucky sometimes tell their teachers that they hope to “draw” when they grow up. But they’re not talking about a career as an artist; they’re talking about drawing a government check. These kids weren’t programmed like that at birth; they were taught something destructive by their communities. A world where very few work, where many use (or deal) drugs, where more go to prison than to college, changes the expectations of all but a few remarkable souls. And with destructive expectations comes destructive conduct.

Appalachia teaches us that breaking people out of bad communities has more promise than changing those communities wholesale; that encouraging family stability — or at least not discouraging it through the tax code or needless incarceration — promotes upward mobility more effectively than transfer payments; that educating people for employment somewhere other than the depressed local labor market is a better investment than short-term public works; and that helping kids overcome low expectations creates more hope than giving money to those kids’ parents.

As a policy agenda, this is a little less ambitious than transforming the mountains from a den of poverty into an engine of economic growth. But if the failures of Appalachia are any guide, a narrower policy agenda might actually serve the poor — white and black alike.

The scale of the investment is staggering. From 1965 until 1981, when the federal government began to scrutinize the cash flowing to Appalachia, federal appropriation to the ARC exceeded $1 billion (in today’s dollars) every single year. Even today, Congress sends about $80 million to the ARC; no other regionally focused entity spends more. As late as 2000, Appalachians received more federal money per capita than average, despite their minimal cost of living and the low number of federal employees in the region.

Twenty years after the ARC’s founding, the New York Times reported that the nation had spent billions on Appalachia with little gain. Its employment gap had persisted and even widened — during the worst of times, the unemployment rate was as much as five percentage points higher than the national average. Economically depressed Central Appalachia lost 26,000 jobs at a time when the U.S. economy added 7 million.

That was in 1985. Today, the inheritors of Katznelson’s affirmative action for whites occupy the lowest rungs of the socioeconomic ladder. West Virginia, Kentucky, northern Georgia, and South Carolina all nabbed more than their fair share of federal aid, but now they are among the poorest parts of the country. Inequality has grown faster in West Virginia than in any other state. When the New York Times compiled a national quality-of-life ranking, six of the bottom ten counties came from the same small corner of southeastern Kentucky.

Residents of these states suffer the worst consequences. In many Appalachian counties, inhabitants can expect to live only 67 years, more than a decade less than the average American. In the heavily white Rust Belt enclaves of Indiana and Ohio, children born poor have only a 6 percent chance of becoming wealthy, significantly worse than those from Newark (9.4 percent) or Salt Lake City (11.5 percent).

Alongside the grim statistics is a spiritual poverty more difficult to measure but easier to see. There’s the high-school teacher who has only once had a class without a pregnant student. The kindergartner who arrives at school in January without a shirt, so embarrassed that he forgot to put one on that he refuses to remove his thin jacket. The teenaged mother who lost track of her child — “She acted like she had lost her car keys,” her teacher later told me. Authorities found the baby with distant relatives more than 600 miles away. Behold the “winners” of FDR’s and LBJ’s brands of affirmative action.

Not all of these anti-poverty efforts failed. Many whites rode the GI Bill to a great education or assumed mortgages for wealth-building property when most blacks couldn’t. But there are millions of people whose family tradition is destitution: Their forebears were day laborers in the antebellum slave economy, sharecroppers after that, and then miners and steelmen until they couldn’t find jobs at all. The Treasury opened its wallet to change that, building homes, roads, and power plants in the hopes that some could escape the poverty trap. Is it shameful that these efforts were expended primarily in a way that excluded the black population? Certainly. Yet the failure of the effort gives us ample reason to question the wisdom of federally led development efforts no matter the intended beneficiaries. Government cannot create a sustainable economy, no matter how hard it tries. And traditional welfare, while defensible as a way of alleviating immediate deprivation, too often fails to place people on the road to self-sufficiency.

Yet there is more to glean from our government’s efforts to help Appalachia than a renewed skepticism of government aid. We’ve learned, painfully, that for the multigenerational poor, home might be the worst enemy. Appalachian loyalty to the land is the stuff of legend, yet the stubbornness of poverty in the region means that those who stay risk being poor forever. When the government paved thousands of miles of roads in Appalachia, it hoped to provide employment for the masses and infrastructure to sustain future economic growth. But the best and most lasting effect of those roads was to give people a faster way out. If we cannot improve the urban ghetto or the mountain hollow — and the evidence suggests we can’t — then the best anti-poverty program is a ticket to somewhere else.

Migration works not just because some areas suffer; it works because many areas don’t. Take, for instance, two small towns in southeastern Kentucky — Hazard and London. Each suffers from high rates of poverty. Yet Hazard’s children are more than twice as likely to earn a high income — much likelier than children from nearly every major American city. Subtle differences give clues about why. In Hazard, poor people are more likely to live in mixed-income neighborhoods, and intact families are the norm. London children, on the other hand, more often experience broken homes, and the poor live in income-segregated neighborhoods. As the eminent sociologist William Julius Wilson has argued, these segregated neighborhoods send thousands of subtle signals about acceptable (or unacceptable) behavior. Young students in eastern Kentucky sometimes tell their teachers that they hope to “draw” when they grow up. But they’re not talking about a career as an artist; they’re talking about drawing a government check. These kids weren’t programmed like that at birth; they were taught something destructive by their communities. A world where very few work, where many use (or deal) drugs, where more go to prison than to college, changes the expectations of all but a few remarkable souls. And with destructive expectations comes destructive conduct.

Appalachia teaches us that breaking people out of bad communities has more promise than changing those communities wholesale; that encouraging family stability — or at least not discouraging it through the tax code or needless incarceration — promotes upward mobility more effectively than transfer payments; that educating people for employment somewhere other than the depressed local labor market is a better investment than short-term public works; and that helping kids overcome low expectations creates more hope than giving money to those kids’ parents.

As a policy agenda, this is a little less ambitious than transforming the mountains from a den of poverty into an engine of economic growth. But if the failures of Appalachia are any guide, a narrower policy agenda might actually serve the poor — white and black alike.

– J. D. Vance, a graduate of Yale Law School and a Marine Corps veteran, is working on a book about the social mobility of the white working class. He can be reached through his Twitter account, @jdvance1. For more on the plight of Appalachia, see “Left Behind,” Kevin D. Williamson, National Review, December 16, 2013. This article originally appeared in the September 22, 2014 issue of National Review.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Thank you for sharing your insights. Please feel free to offer new ideas!